Lloyd Pollak An autobiography

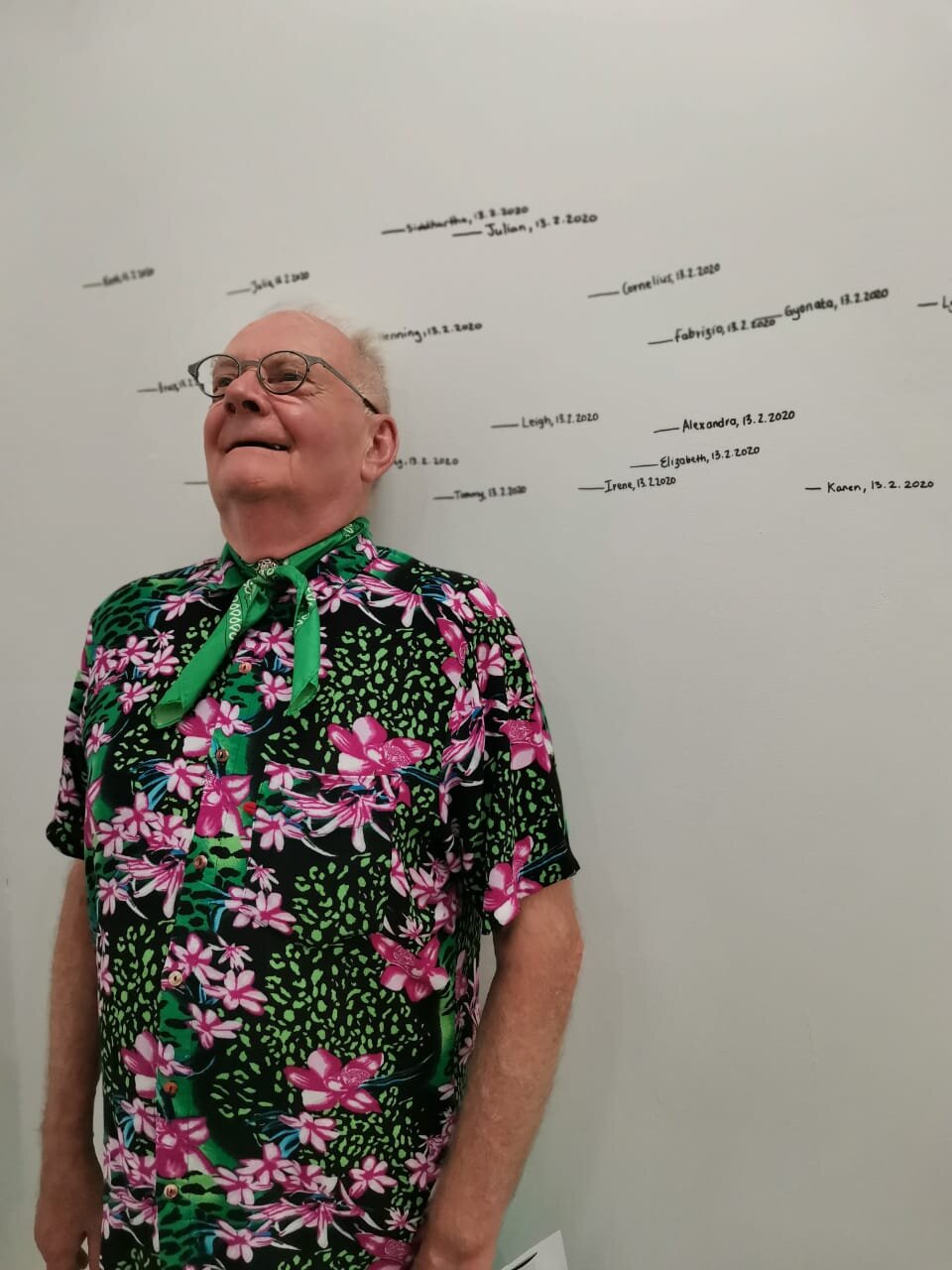

Being an unconventional individual, I am constitutionally incapable of writing a conventional C.V. Suffice it to say, I was born in Cape Town and here I remain. My family were rich, but now that the money has long gone, I still combine extravagance with impecuniousness. My parents spoilt me, and, from the age of 12 took me annually on extravagant trips to Italy, France, Spain, Holland, and Austria which exercised an immense influence of my tastes and proclivities.

Although I was lonely; my brother is mentally challenged and has lived since 1949 in a National Health home in England, my cousin (who lived with us) lost his life in a car accident days before his 21st birthday, and my parents were inveterate socialites who were out every night. There was little family life. I was always, like my father, an avid animal lover, so I lived a cossetted existence in a private menagerie surrounded by innumerable beloved cats, dogs, budgies, tortoises, guinea pigs, rabbits, and an aviary full of birds of every variety. I think because I enjoyed such closeness with these playmates, I admire their unstinting devotion and lack of guile, and like and trust them far more than people who are altogether a far trickier proposition.

I won’t mention school as it bored me from start to finish and, as Sir Winston Churchill remarked “it seriously interfered with my education.” I was a dedicated bookworm and my adult life began when I went to the University of Cape Town where I suddenly found myself surrounded by like-minded people and enjoyed many a rewarding friendship. Originally I intended to study English as that was the only subject at which I excelled, but as at that time, the English department was staffed exclusively by fuddy-duddy, pedantic, geriatrics who should have been put out to grass ages ago. So, I majored in French instead. The lecturers were all so uniformly stimulating, provocative and enlightening and they somehow dispelled the miasma of provincialism and parochialism that enshrouded that institution, then as now.

In 1967 after completing my military service, I spent the year working and travelling in Spain, Italy, France, Austria, Germany, Holland, and Belgium. At the end of that year I proceeded to the Sorbonne where I studied Comparative Literature (a discipline that does not appear to exist here). In May of the next year, 1968, the student revolution erupted, so although it was a wildly exciting experience that completely transformed my narrow South African views on everything, it proved far too disruptive for any academic achievement, so, on my return to South Africa, I decided to engage with the real world and started work as a copywriter in Johannesburg.

Those were the days when Joey’s was still Joey’s, and when, as David Ogilvie said, “Advertising was the most fun you could have with your pants on.” It was the ideal calling for misfits, aspirant writers, non-conformists, eccentrics, rebels, freaks and weirdo’s – all categories into which I easily fit. Those are the years I remember with the most affection – the long bibulous luncheons, the wild parties, the fascinating personalities and – most of all - the fun, fun, fun! As a copywriter, I worked in Cape Town, Johannesburg, London, Dublin, Sydney, and Melbourne for the next twenty-five years. Then I became disillusioned, and I found the whole occupation trivial, exploitative, and capitalistic.

Mercifully an aunt of my died precisely on cue, leaving me sufficient money to spend 16 months doing the Victoria and Albert Museum Diploma at the Study Centre for the Fine and the Decorative Arts in London. I came first in my class with distinctions in three of the four disciplines. I then returned to Australia where I ran courses on antiques for Sotheby’s in Melbourne and Sydney, and slowly I extended my repertoire to include art.

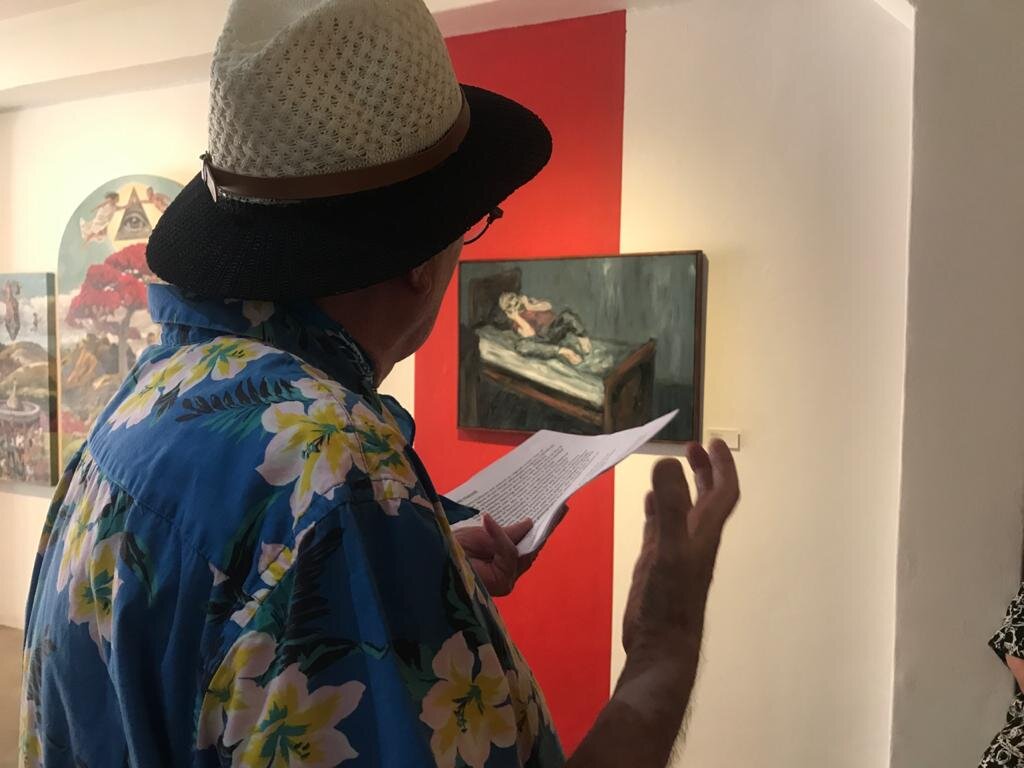

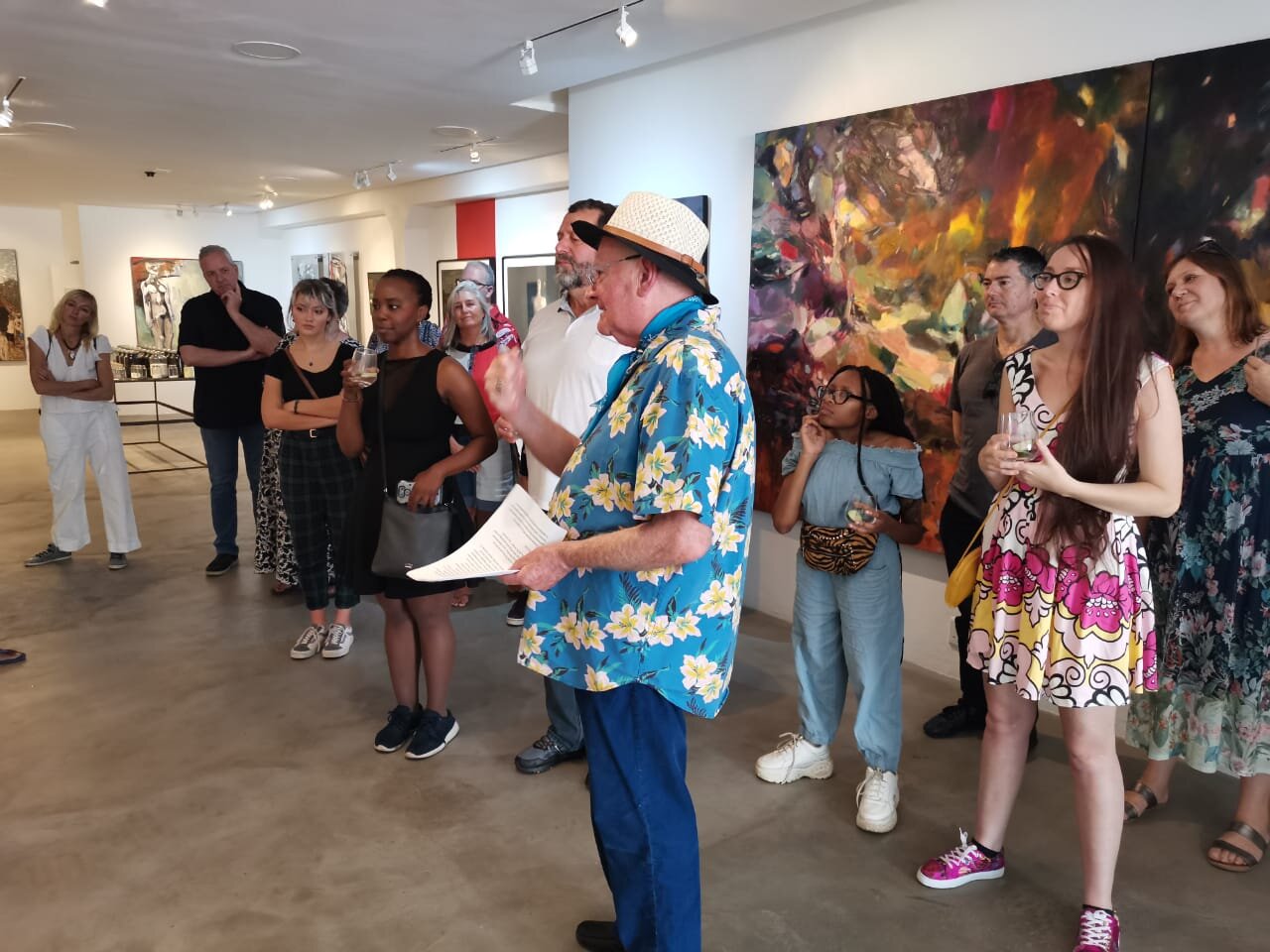

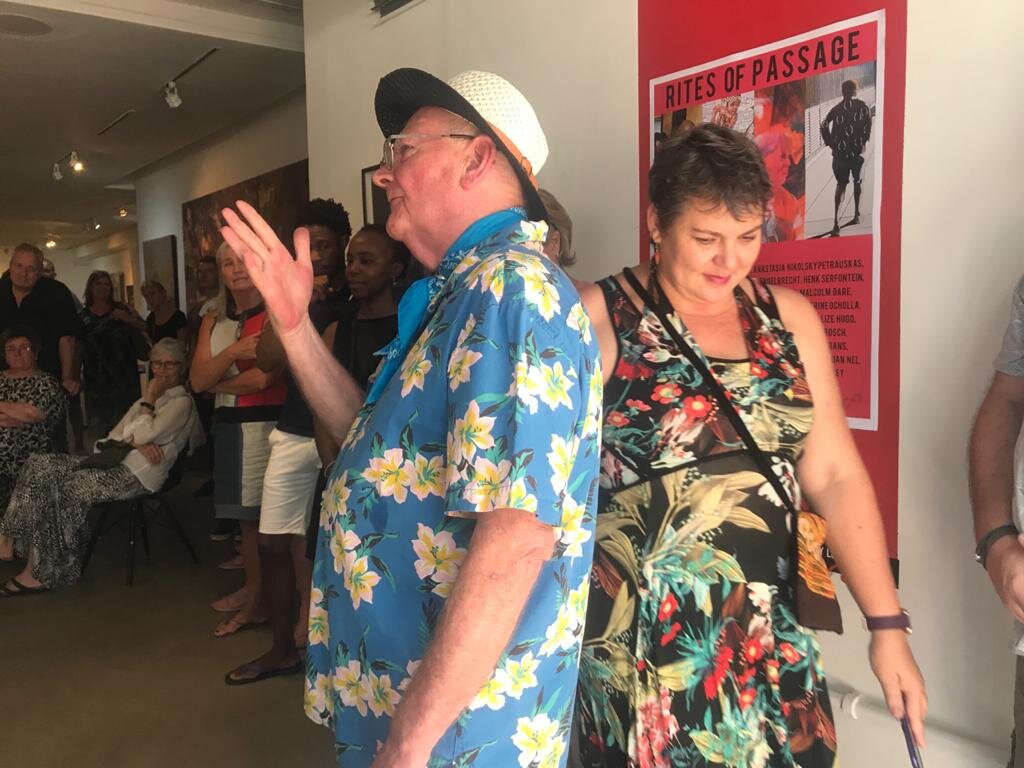

After the ANC Victory (I was never an ‘exile’: I left the country out of political distaste, boredom and a sense of adventure) I returned to Cape-Town, and lectured on the fine and decorative arts for the Friends of the National Gallery, the Labia Museum and the Fine and Decorative Arts society in Cape Town and Johannesburg. For years I worked as an art critic for the Cape Times, and then the Art Times and Art throb, writing literally hundreds of reviews. I also started compiling catalogue essays.

I wrote my first published book on Gail Catlin and her liquid crystal medium in 1999, then I was commissioned by Myra Osrin (then the Director of the Cape Town Holocaust Centre), who admired my journalism, to write a book celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Holocaust Centre. Although I secured no cooperation from the artist, I also wrote – with immense difficulty – a weighty tome on Simon Stone, which was published by SMAC gallery on the occasion of his Standard Bank Retrospective in Johannesburg in 2013.

Since June of 2015, I have abandoned lecturing and writing articles, as they ceased to present any challenge whatsoever, and devoted myself almost entirely to writing monographs on cutting-edge talents on the cusp of fame and glory. I found this work far more challenging as there is so little written on these artists, that the subject was virtually virgin soil. I have already published monographs on Kate Gottgens, Matthew Hindley, Barend de Wet, Jody Paulsen, Max Wolpe, and Asha Zero besides dozens of articles on my own personal website, lloyds-artbeat.co.za

The single most controversial piece I ever wrote was an excoriatingly vituperative dismissal of the work of Vladimir Tretchikoff penned at the time of his Retrospective at the National Gallery. As an art critic I firmly believe I have only one loyalty and that is to my readers. I do not see championing the cause of South African art as my role: my duty is objective appraisal, not promotion, particularly as so much of our art is derivative, inferior and vastly over-rated. I do not want to end up like the Art’s programs on Fine Music Radio which shower indiscriminate praise on everything. This is of no help to the listener.

Al Alvarez attacked “the cult of gentility” in English culture, and I also believe art criticism in South Africa is bedevilled by timidity, politeness and good manners. If I am well-known for anything, it is for calling a spade a spade, and daring to defy the politically correct thought police and provide my own honest opinion with no holds barred. Nothing more can be asked of a critic.